Combat the Effects of High Inflation on Donors’ 2023 Giving

Please enter your information to receive this free article.

Written by Peter H. Congleton for Planned Giving Today

Any old mariner familiar with the rising and ebbing of the tides, the shifting winds, changing currents, and the myriad perils of the sea, will advise you to “always keep a weather eye out.” That analogy is fitting for nonprofits today, especially those simply trying to stay afloat in the rough seas stirred up by the pandemic.

Preoccupied as most nonprofits may be with meeting the pressing financial challenges of the day, there’s a good chance that their short-term concerns may have caused them to overlook new challenges looming on the horizon. Yet within those dark clouds there may actually be an opportunity that could fill their sails, avoid foundering, and speed them on their voyage.

For decades now, we have heard predictions of the massive intergenerational wealth transfer that is largely associated with the baby boom demographic. Upon this premise, the fundraising discipline of planned giving, now gift planning, has developed techniques and vehicles by which nonprofits can better harness a charitable share of that inevitable bounty through the appreciated assets, trusts, and estates of their most loyal supporters.

As the field of planned giving has evolved to better accommodate the changing circumstances of prospects and donors, constraints on staffing budgets have also relegated gift planning to more of a collateral duty in most development shops.

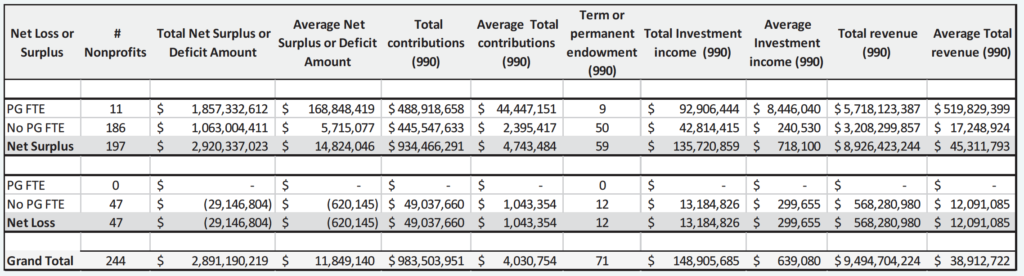

In a recent survey of 244 New Hampshire nonprofits reporting gross receipts greater than $2 million, I found that 42 (17 percent) of those nonprofits have a Legacy Society, recognizing donors who have informed them of future gifts they have included in their trusts or estate planning. Fifteen (6 percent) of those surveyed offer a selection of planned giving options on a dedicated webpage, but only eleven (4.5 percent) have a full-time planned giving professional on staff.

In addition to the recent CARES Act and SECURE Act, other legislative bills have already been introduced in Congress that could dramatically affect the gift plans that our wealthier donors may currently have in place. Wealth managers and tax advisors report a growing concern on the part of their clients in anticipation of:

For the 95 percent of nonprofits which rely on donors’ advisors to recommend charitable giving options to their clients, that passive approach could prove costly. What incentives will those advisors have to make such recommendations? And who will be answering the phone or the email at the nonprofit to offer the best suggestions for the donors’ advisors to review?

On two separate occasions during my three decades as a planned giving director, had I not answered the phone, asked the right questions, made appropriate suggestions, and followed up with the donor, one nonprofit would not have received a $6.3 million endowed scholarship fund. This was a blended gift of cash and revocable trust distribution, and another would not be awaiting eventual receipt of an $11 million property through a will that would not have been valid without personal interaction and follow up. $17.3 million in charitable giving would likely never have materialized if only two calls had gone unanswered, or an untrained staff member had answered the phone, not followed up appropriately, or dismissed the inquiry altogether.

From the perspective of a would-be donor trying to gather information for planning a charitable gift to any of the 244 New Hampshire nonprofits in the sample, my survey found that 232 (95 percent) of the nonprofits referred planned giving inquiries to a non-planned giving dedicated staff member.

For the nonprofits that actually offered a phone number, my calls to learn more about their gift planning offerings typically went to voicemail. Only 6 of 25 staff members ever returned the call, and only one did so promptly (on a Saturday morning, no less). One nonprofit staff member hung up on me when I suggested that a drop-down online giving form for “Bequests” might not be entirely effective or appropriate.

Some of my general observations from this exercise suggest that most nonprofits tend to be more reactive than proactive when it comes to engaging with their constituencies around the gift planning process. Here are some prevalent examples:

Too few nonprofit leaders seem willing to invest in the current and ongoing value that gift planning can offer to its charitable mission and the organization’s bottom line.

Nonprofit decisionmakers and budget masters either overlook the short-term advantages to long-term relationships in the fundraising mix, or more often than not, fail to recognize gift planning’s relatively high return on investment compared to other fundraising activities. In fact, of the 244 nonprofits surveyed, the 98 (40 percent) which reported “Fundraising” 1 activities on their most recent IRS Form 990’s, collectively spent $6.5 million to net $1.4 million and 25 (10 percent) of those reported an average loss of $84,862 in this category.

Although it is difficult to readily determine from a 990 Form what portion of individual gifts found in “Total Contributions” are classifiable as “planned gifts”, experience shows that it can be variable but is often substantial. I have worked at organizations that regularly received more than 50 percent of their total contributions from planned gifts such as bequests and trust distributions, and legacy society members invariably outpaced other donors in both participation and lifetime giving.

Judging from the survey summary on Page 10, “Total Contributions” and endowment or “Investment Income” may have kept many of the “Net Surplus” nonprofits afloat or could have steered any of the “Net Loss” nonprofits clear of the shoals.

A sea change of tsunami proportions appears to be on the horizon. It would behoove nonprofits everywhere to pay attention to what their donors may be thinking and doing in response, making sure that donor-facing staff are well-trained and well-prepared for the coming challenges and inherent opportunities.

Whether hiring experienced Planned Giving FTE’s or paying consultants to bring the necessary expertise and experience to coach and train existing staff, it is clearly time to fix our eyes on the horizon, check the rigging, trim the sails, and point our bows into the next oncoming wave.

Your message was successfully sent

Our customer support manager or technical department representative will contact you within 24 hours.

Please enter your information to receive this free article.